As global demand for renewable energy continues to rise – driven in part by countries’ Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) and the expected savings with renewable technologies in the future – South America stands out as a global leader in both mineral reserves and renewable energy use. The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that, globally, the demand for critical minerals will increase six-fold to achieve net-zero emissions.

South America holds a significant share of the world’s critical mineral reserves, including sizable quantities of nickel, lithium, cobalt, and copper. Chile, Argentina, and Bolivia together form the world’s ‘Lithium Triangle,’ constituting roughly half of the world’s lithium reserves. On the energy side, the region is already a leader: renewables account for about 60% of the regional energy mix, with hydropower providing the majority of electricity in several countries. Solar and wind capacity are projected to double by 2030, while the coal and oil use is expected to decline – even as oil remains the dominant fuel in transportation. South America is positioning itself at the center of the global shift away from fossil fuels.

The region’s long-standing reliance on mining offers an explanation. Between 1990 and 2000, South America attracted about one-third of global mining exploration investments. Today, mining accounts for 10% or more of GDP in countries such as Peru and Chile. Yet, South America is also home to 40% of the world’s biodiversity, half of its tropical forests, and about 10% of the world’s Indigenous Peoples. As the search for more critical minerals grows and South America’s mining activities expand, it has increasingly threatened the region’s natural resources and indigenous peoples, undermining the ecological and social wellbeing of the communities that inhabit these areas.

In response to the tension between the growing need for minerals and healthy ecosystems, the concept of a “Just Energy Transition” has been rapidly gaining momentum worldwide. Grounded in equity and fairness, it emphasizes the rights and needs of environmental defenders, Indigenous Peoples, and historically marginalized communities who have been notoriously overlooked throughout history. A just transition acknowledges that different communities experience energy shifts in unequal ways, and therefore requires context-specific approaches through a lens of intersectionality. These might include ensuring meaningful community participation in renewable energy job creation, or channeling affordable electricity into improved education and infrastructure, among other things. Yet the broadness of the term “just” makes it both flexible and difficult to operationalize, without clear steps for action or avenues for accountability.

The demand for critical minerals carries deep ramifications for human health. Mining does not only pollute water and erode ecosystems; it shapes the conditions under which people live, work, and sustain themselves. In this context, public health means not only the absence of illness but also the safety of infrastructure, the security of food and water, preservation of cultural identity, and the ability to live without chronic stress. In South America, where natural resource wealth overlaps with high biodiversity and Indigenous territories, these impacts are acute. In a much broader sense, critical mineral mining can exacerbate crises around land tenure and management, food insecurity, and mental health. As the world moves rapidly towards the scaling and deployment of renewable energy, it becomes increasingly important to consider the public health consequences posed by the mining conducted earlier in the process.

Environmental Pathways to Health Risks

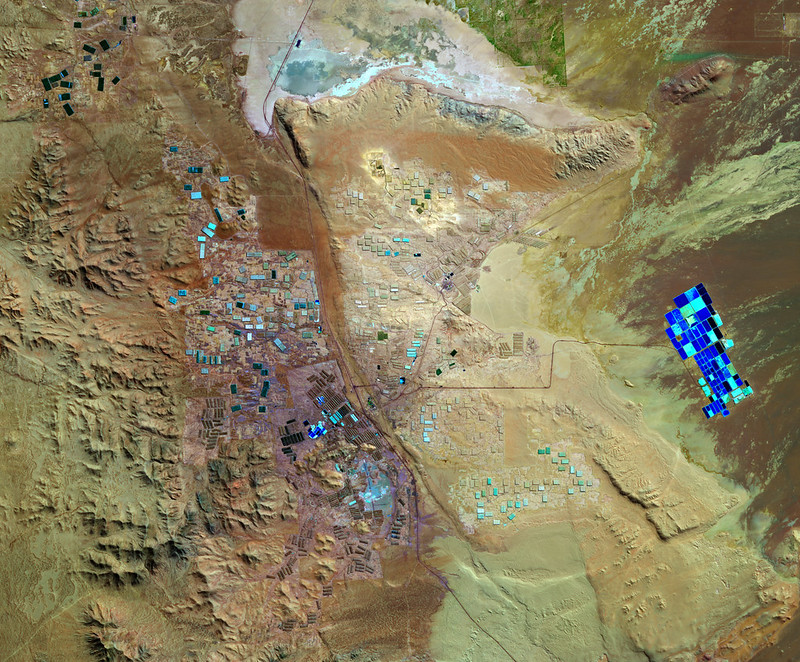

The most immediate health impacts of critical mineral mining come through its effects on nearby land, water, and air. The example of the extraction of lithium in the Lithium Triangle illustrates this clearly: producing a single ton of lithium requires up to 500,000 gallons of water. In one of the driest places on Earth – the Atacama Desert – this massive withdrawal has lowered water tables, forced fresh and salt water to mix, and depleted sources of water for human and animal consumption. The Indigenous communities that live in the Atacama are left facing water insecurity, and, in turn, become reliant upon private tankers for delivery, with dramatic consequences for their future livelihoods.

The environmental impacts from critical mineral mining can lead to the acidification of water, groundwater pollution, erosion, and aquatic toxicity and biomagnification throughout the food chain. The residual mine tailings produced through mining and their impacts on health are well documented. Research also shows that countries with high amounts of copper also suffer from negative health ramifications due to insufficient management of mine closures – such as in Peru and Chile. In the two countries, mine tailings were deposited into the rivers up until the end of the last century, with the communities still navigating the effects today. Cerro de Pasco, Peru – described as one of the most contaminated places in the world – remains a case in point. The chronic exposure to heavy metals, including lithium, have predisposed children to suffer frequent nosebleeds, chronic stomach pain, skin conditions, mood swings, and vision problems.

Mining also worsens air quality in the surrounding regions. The dust from roads and tailings piles, combined with the greenhouse gas emissions from smelting and transport, contribute to higher rates of respiratory disease. Communities in Peru’s mining corridor and copper belts in Chile report daily exposure to particulate matter that exacerbates asthma, pulmonary illnesses, and chronic diseases. The respiratory effects of critical mineral exposure are well documented: cobalt has been linked to heart problems, nickel is acknowledged as a carcinogen, and lithium can also damage the kidneys and thyroid while contributing to developmental disabilities.

Land Management and Occupational Hazards

Beyond direct pollution, critical mineral mining reshapes how people live, work, and move within their spaces, with overarching public health ramifications. Migration is one such pathway: some families are forced to leave degraded lands when water scarcity or contamination makes farming impossible, while others migrate towards mining areas in search of jobs. For example, in Peru’s Madre de Dios, a number of Andean communities have moved towards the Amazon to partake in often illegal gold mining, trading a paycheck for long-term harmful environmental exposure. Both types of migration affect health, ultimately – leading to food insecurity and loss of social networks, while faced with inadequate working conditions.

The transportation infrastructure around mining also poses risks, particularly in an uptick of illegal mining. Over just one month in 2019 in Peru, more than 11 accidents were reported as copper exports flooded the partially paved highway with heavy trucks; extraction booms can translate to immediate occupational dangers for both drivers and nearby communities. The mineral dust and exhaust from the traffic further worsened air quality, while the degraded roads limited safe mobility and access to additional external services.

Deforestation linked to mining compounds the social challenges. In Brazil, about 10% of Amazon Rainforest loss has been attributed to copper and nickel projects. This loss undermines local food systems, reduces access to clean water, and increases the spread of infectious diseases as natural ecosystems are depleted. Indigenous and rural communities have often borne the brunt of deforestation in South America, given their proximity to extractive areas – as the original stewards of the land, this environmental loss also destroys their nutrition, medicine, and other cultural practices tied to the earth .

Land management challenges are further shaped by conflict. According to a 2022 study, persistent disputes between local communities and governments over natural resource governance, made more accurate by the rising demand for critical minerals, have limited the ability of states to enforce stronger environmental protections. The result is a cycle where communities closest to mines, often Indigenous or rural, experience the downsides to mineral extractions yet do not reap the social benefits or economic growth. The same populations bear the brunt of attacks on environmental defenders in Latin America, which have increased alarmingly over time. This disconnect feeds into a negative feedback loop that further impoverishes communities, and sparks backlash against both local governments and mining companies, straining governance systems meant to regulate land use and provide direct services.

Food Sovereignty

Areas where mining and agriculture overlap often tend to show higher levels of soil contamination, raising the risk that heavy metals and other pollutants enter crops and livestock, later biomagnifying throughout the food chain. This can be easily seen as a direct threat to food sovereignty by undermining the safety and productivity of local agriculture.

In Bolivia, Indigenous communities around the Salar de Uyuni have long sustained themselves through the cultivation of quinoa and pastoral farming. As of 2018, about 13,000 families had income through quinoa farming, over eight times the number of jobs that would have been created by lithium extraction in the same area. Yet, lithium operations demand vast quantities of water, worsening scarcity in an already arid landscape and decreasing the resiliency of the area against climate change-caused droughts in the future. As a result, both the food production and communities' rights to clean water and healthy ecosystems of these native stewards are threatened.

Across the border in southern Peru, the copper-rich department of Moquegua contains elevated levels of metals in the soil, directly contaminating the food supply. Over time, competition over water has intensified to the point where the local water management has been criticized for prioritizing mining operations, fueling social conflict between the communities and extractive industries. These pressures limit the region’s adaptive abilities to climate change while reducing the breadth and health of local food systems.

Mental Health

Mining has been noted to have profound and diverse effects on mental health and the individual, society, and community levels. Alongside global environmental changes, ecoanxiety manifests itself as a result of the loss of identity tied to environmental wellbeing, perpetuated by less access and decreased dependency to the natural resources that supported the existence of communities till now. In the area of Putaendo, Chile, residents expressed eco-anxiety at the prospects of an early-stage copper mining project, expressing a cultural and ontological loss at the lack of control within their environment.

Apart from the physical occupational hazards, emotional stressors have also been associated with mine workers, particularly around the perception of a negative quality of life, only to be exacerbated by the long hours, high demands, occurrence of injury, and likely consumption of substances all contributed to anxiety, depression, somatic disorders, and general psychological stress. Studies also show that increased distress has been recorded in areas with higher contamination from mining.

In Ecuador, the Shuar people living near the Panantza copper mine have been in conflict with authorities for a number of years, including their forced displacement by the military in 2017. The forced eviction and resulting migration has resulted in depression, elevated heart rates, tremors, all of which are evident in the next generation of children. Addressing the harms of mining from critical minerals requires more than just an assessment of the ecological and environmental ramifications, but the social and mental costs as well.

While renewable energy is clearly the way forward, the immediate outputs of critical mineral mining can have long-term effects, particularly in the case of South America, which is well positioned to be a leader in the race against climate change. These adverse outcomes touch all facets of what we consider to be public health rights: the right to a clean and natural environment with an abundance of resources, governance of land that safeguards local ownership and livelihoods, autonomy of communities in securing food access and consumption, and the social and emotional wellbeing that comes from being rooted in place and space. Unfortunately, the reality falls far short of that, with the most marginalized who contribute the least to climate change bearing the brunt of the repercussions. Unless bold and honest leadership and governance seek to address the resulting social and cultural ramifications, the just energy transition risks reproducing the same extractive mechanisms that have undermined health for all this time.

Supriya Sagadopan is a conservationist and development practitioner passionate about the intersection of environmental policy and the impact on communities. Her work focuses on improving land management and governance practices with an emphasis on deforestation through policy recommendations and advocacy.