Ecuador, nestled within the biodiverse, rich region of the Andes and the Amazon basin, is especially susceptible to the impacts of climate change. The country experiences a range of climatic hazards, such as floods, droughts, and landslides, which pose significant risks to both rural and urban populations. Indigenous communities bear a disproportionate burden of these climate-related challenges as they work as custodians of ancestral lands and traditional knowledge systems, they are deeply interconnected with their natural surroundings, relying on ecosystems for sustenance and cultural identity. However, their intimate relationship with the environment also renders them uniquely vulnerable to its degradation.

Being a land defender is a dangerous affair. According to Global Witness, 85% of defenders assassinated worldwide in 2024 were from Latin America. That has not stopped Indigenous activists, who had their hands full last year successfully stopping the project of building a maximum security prison in the Amazonian city of Archidona; contesting the operations of Canadian mining companies ‘La Plata’ and ‘Solaris’ in different territories for skipping Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC); and asking for compliance with the results of the 2023 referendum where 59% of Ecuadorian voters said ‘yes’ to stop drilling in the ITT oil field in the Yasuní National Park - the most biodiverse place per hectare in the world and home to two Indigenous communities in isolation.

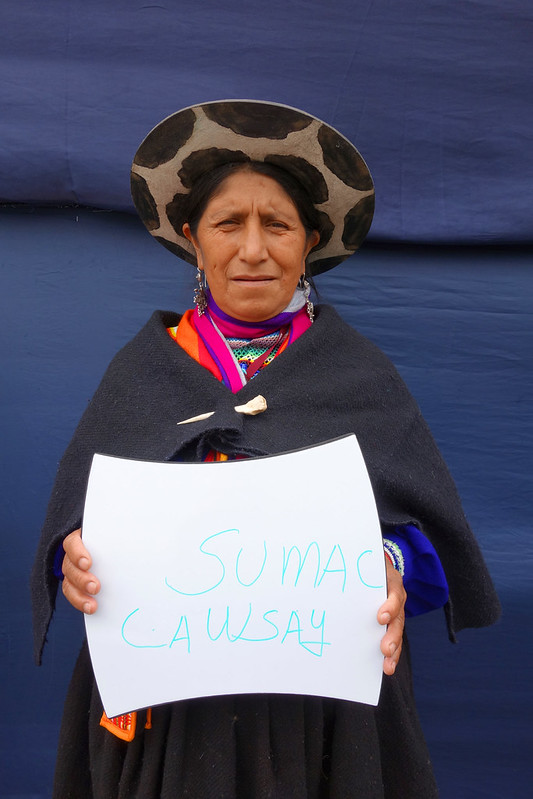

Ecuadorian Indigenous women are recognizable as faces of the land defender movement worldwide and stand out in different arenas as political leaders, public figures, and heads of conservation initiatives. In the early 2010s, women from the Shiwiar, Kichwa, Sapara, Waorani, and Shuar communities were central figures of a march on Ecuador’s capital. They brought with them the political-economical-cosmological proposal of Kawsak Sacha, or ‘living jungle’ as an alternative to the XI oil round, a public tender started in 2012 that was to concession off around 8.9 million acres in the south-central Amazon to oil exploration from Ecuadorian and international companies.

Even though the Indigenous fight for their territories is collective, women in particular face intersecting forms of discrimination and marginalization that amplify their susceptibility to climate change impacts. As primary caregivers and providers within their communities, they often bear the brunt of environmental disruptions, grappling with threats to food security, water access, and health. Moreover, entrenched gender inequalities and systemic barriers limit their agency and access to resources, constraining their ability to adapt and respond effectively to changing environmental conditions and undermining their resilience in the face of climate-related challenges. Numbers show that 67.8% of Indigenous women in Ecuador suffer from gender-based violence, making them one of the most affected ethnic groups. As such, addressing the disproportionate effects of climate change on Indigenous communities requires not only acknowledging their unique vulnerabilities but also dismantling the structural injustices that perpetuate inequality and marginalization.

Three women from the Sapara and Waorani communities agreed to be interviewed and gave insight into their relationship with their territory, the threats they face, and the solutions they are bringing to the table. It is important to note that the women interviewed are not mere informants but thinkers, defenders, and builders of knowledge to stimulate reflection on this issue.

Interviewees 1 and 2 are members of the Sapara community in the province of Pastaza, Ecuador, which once saw their territory span approximately 2.9 million acres in Ecuador and Peru. They now live across about 914,289 acres (about 133,436 acres legally recognized by the Ecuadorian government as being under Sapara community tenure) and have seen their community’s numbers decrease drastically to around 200 members in Ecuador. Both interviewees acknowledge the importance of growing up amongst ancestral knowledge in their journey to becoming environmental defenders, hearing stories about the first arrival of the military and oil companies to their territories, which in turn prepared them for the years of struggle to annul contracts given to two Chinese oil companies in their territory.

In Interviewee 1’s experience, once oil companies enter the territory, the jungle loses its spirit. In her words:

“When I went to the northern Amazon, I felt an emptiness, like the one you feel in an empty room. I saw all the [oil] wells, the burners, and the plants that were still there but which felt soulless. The spirits we believe in did not exist there. When I returned home, I felt the jungle calling. It felt alive.”

The third interviewee is a member of the Waorani community, which stewards around 1.6 million acres of territory and has 3,000 members across 32 communities. Her path to her involvement in the defense of her territory came from growing up with women who have been deeply involved in this fight. Her grandmother was Dayuma, a recognized Waorani leader, and her mother was one of the promoters for creating the Waorani community organization. The Waorani have also fought to protect their territories from oil companies, winning a ruling from the court in Pastaza, which recognized the violation of the right to prior consultation and self-determination in 2019. However, five years later, the government has still not complied with the court's ruling.

Indigenous women's increasingly important roles in environmental defense have also made them important political actors. Important women’s organizations from the Sapara and Waorani communities started forming in the 2000s in response to the backlash against some existing, male-led community organizations for bad fund management, lack of consultations, and corruption cases. Some of those organizations were formed primarily to provide a way for oil companies to ‘negotiate’ with communities, resulting in women's power and role being invisibilized.

Gaining access to political spaces has not been the only tactic Indigenous women employ to defend their territories. Interviewee 3 mentioned Indigenous community enterprises as part of their bid to keep communities resilient and also have stable livelihoods. AMWAE (Association of Waorani Women from the Amazon and Ecuador) hosted a project called “Chocolate para la Conservación” (Chocolates for Conservation) to prevent indiscriminate hunting. It benefited around 400 families in 8 Waorani communities. Interviewee 2, a young Indigenous woman, harnessed the importance of ancestral knowledge, which she works on recovering alongside other youth from her community.

Interviewee 1 is part of Colectivo Tawna, which uses cinema to tell stories from its communities. Through its films and documentaries, it illuminates a reality not usually shown when people from outside come to film them, which she feels usually romanticizes life in Indigenous communities. Cinema and storytelling, she says, can help women find their voices.

Ecuador’s status as a plurinational and intercultural State was achieved with the 2008 constitution, establishing a broader catalog of collective rights, including self-determination per each community’s rights, practices, and ancestral knowledge. Nonetheless, existing policies remain insufficient. Article 171 of the new Ecuadorian constitution states that Indigenous communities have jurisdiction to solve internal conflicts; however, it has proven to be insufficient when it comes to gender-based violence as sometimes women are unaware of the extent of their rights as members of a community. Lacking also, the interviewees say, is more support for Indigenous-led community enterprises, respect for existing public policies and court rulings, access to essential services for communities, and more alignment amongst different Indigenous nationalities to share in the responsibilities of resilience and protection of their territories.

A significant leadership gap exists in political participation. Despite women being the primary actors in rallies, protests, and mobilizations, their role has not been recognized as politically relevant, and they still find difficulty in reaching top leadership positions in community and national Indigenous organizations.

Some recommendations to alleviate these issues have been proposed, including: engaging Indigenous women in negotiations around climate justice by integrating them into conversations instead of siloing them; and incorporating a gender lens in all policies relating to climate change and Indigenous peoples; advocate for FPIC in all projects and decisions related to the territories of indigenous communities, especially as the energy transition pushes for more mining and other projects in indigenous lands; and develop strategies for quality social services to reach Amazon communities to avoid creating vacuums which extractivist companies or organized crime can exploit. But courthouses in Amazonian provinces of Ecuador sometimes lack the technical capacity to abide by the regulations created for FPIC or gender-based violence cases.

Indigenous peoples have an intrinsic connection with nature and the forest. They understand what species live within it, when to take from the forest, and when to give back. Hearing the stories of Ecuadorian women who are exposed to daily threats from the expansion of extractivism in their territories shows their resilience and commitment to this fight. It is a fight they will not abandon, one that concerns their livelihoods, traditions, language, and communities.

There is still a long way to go in terms of supporting them and their movement better. National Ecuadorian policies must have a better gender lens so that the gender-based violence women suffer in all Amazonian provinces does not go unnoticed any longer. At the same time, conservation efforts should always consider the people and women who live within the forest and have guarded them for hundreds of years. Forests, fauna, and people are intertwined, and it is important to have this holistic view when designing forest and biodiversity protection strategies and when countries think of their decarbonization and energy transition plans.

In the words of one of the interviewees:

“As long as there is a single Indigenous person in the world, I believe that he or she will always think of the struggle, of community life, of that generosity and solidarity among Indigenous peoples.”

Find the full version of the policy brief here.

Born and raised in Quito, Sofia Fernandez works in the intersection between tropical forest protection and rights. Her work focuses on movement building and justice in the international climate space.